One hundred and forty nine countries have signed the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide of 1948. These signatories present themselves as the authorities who are committed to and entrusted with preventing genocide.

But none of these countries are held accountable when they ignore the duties set out in the convention. One need look no further than Cambodia, Rwanda, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Balkans, and Myanmar for evidence of a serious flaw in the Convention.

It should be amended to ensure that repeated failures to thwart genocide are remedied. The amendment should be to the Convention’s first Article, which compels signatories to “undertake to prevent and to punish” genocide.

This is not an impossible task. Tanzania, a decade before the Rwandan genocide, entered Uganda in support of a rebel movement there and prevailed. This demonstrates that an alliance of only two third world forces is capable of forcing an army to stand down. Likewise, any number of Convention countries could have done the same in Rwanda, particularly first world signatories with enormous military power. It shouldn’t be forgotten that troops from signatory countries were in Rwanda at the time of the genocide and fled.

The United Nation’s General Assembly, which adopted the Convention, would be an apt forum to debate the proposal I offer here; to shine a light on signatories’ past omissions; and to request their resignation from the Convention if they fail to remedy its shortcomings.

The history

Neither the term nor the concept of genocide existed in the first half of the 20th century, except in the minds of a handful of thinkers. Chief among them was Polish legal scholar Raphael Lemkin.

Lemkin put the notion of genocide forward at the Nuremberg trials against the Nazis. It was later used to draft the Convention. The scholar’s relentlessness heralded what promised to be one of the century’s most important developments in international law, a tale well chronicled in Philippe Sand’s 2017 book “East West Street”.

Despite the adoption of the Convention, signers have never made an effort to end mass killings. This disregards the obligation of signatories to “prevent” genocide. The duty is stated in the title of the Convention and its first Article. But it hasn’t compelled a single nation to lift a finger.

Nations have taken action only after the fact – to punish.

But, those appointed to punish are drawn from the same parties that failed to prevent.

And the argument that punishment deters would-be genocidal killers has proven empty. The timeline shows that Cambodia came after Nuremberg. Rwanda and the Balkans after Cambodia, the DRC after Rwanda, followed by Myanmar.

Punishment did not deter in these cases. Specific deterrence means that those convicted won’t commit genocide again because they are locked up. General deterrence implies that because people are punished, would-be violators will think twice and stop, a doubtful proposition.

Prevention, on the other hand, deters. It leaves nothing left to punish. It saves lives, saves billions spent on punishment, and spares the victims from sorrows that persist for generations.

The obstacles

When signatories fail to prevent genocide, why are there no penalties? Why are there no tribunals to punish those who don’t meet the obligations they’ve signed up to under the Convention?

Signatory countries escape condemnation and get a free pass.

A big challenge is that if punitive measures were included in the Convention aimed at the signatories themselves, few nations would sign. But this raises the question: when signatories can ignore their obligation with impunity what does it say about international law?

In addition, there are instances where the international community is temporarily unaware of genocidal activities. In such circumstances prevention is not possible. But it’s mandatory for signatories to act when credible information emerges. Yet every time the Convention’s foremost provision has arisen, it has been abandoned.

That’s why I would propose that Article 1 be amended to include subsections “(a)” and “(b)”. Article 1(a) would read the same as Article 1 does now. That is to say:

(a) The Contracting Parties confirm that genocide, whether committed in time of peace or in time of war, is a crime under international law which they undertake to prevent and to punish.

Subsection 1(b) would add:

(b) The Contracting Parties further confirm that if they fail to meet their commitment to undertake to prevent genocide, it is a crime of omission and punishable as Complicity under Article 3(e) of this Convention.

“Never again”: an empty phrase

The murky refrain “never again” has faded through the decades like an echo on a dry canyon wall. It is an empty, meaningless phrase. What will the signatories do the next time they are called upon to prevent genocide? History says they will do nothing.

Today, the only framework for punishment in the Convention is triggered by the omissions of its own signatories. Where they fail to make an effort they ought to face proportional punishment for complicity. Amending Article 1 would be a start toward removing the dark stain from what might otherwise have been a praiseworthy and lifesaving instrument of international law.

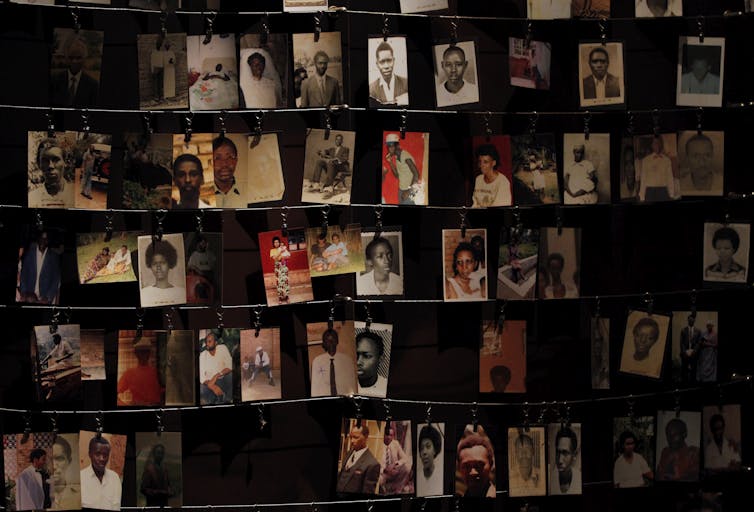

Amending the Convention to include Article 1(b) would be a good way to mark the 25th anniversary of the genocide in Rwanda that’s coming up in April.

Christopher Ayres, Guest Lecturer

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.