Sithembile Mbete, University of Pretoria

South Africa is six months into its third elected term on the United Nations Security Council. Its conduct in its previous two terms has been criticised for the country’s controversial voting record. During its first term, South Africa was accused of supporting rogue states when it voted against resolutions condemning human rights abuses in Myanmar, Zimbabwe, and Sudan. In its second term, it was accused of voting for Western-sponsored regime change in Libya.

Despite these criticisms, the African Union (AU) has endorsed South Africa’s candidature three times and it has received over two-thirds of the vote in the United Nations (UN) General Assembly. This shows that the world views it as a constructive contributor to an organisation charged with maintaining international peace and security.

Being a member of the Security Council matters. This is because it is the most powerful body within the UN.

The UN, founded in 1945, has 193 member states. Its powers are vested in its Charter, which provides for six main bodies in the organisation. The General Assembly is the main forum for deliberation and policymaking. All member states are represented and every September the full membership of the UN meets in New York for the General Assembly session.

Then there’s the Security Council. Its primary responsibility is to maintain international peace and security. Its decisions are binding on all member states and it’s the only body that can authorise the use of force to maintain international peace and security. This makes it arguably the most powerful international forum in the world.

The membership of the Council reflects global power dynamics at the end of the Second World War. It has 15 members – five permanent and ten that are elected by the general assembly for rotating two year terms. All have one vote in the Council. But the permanent members – the US, UK, France, Russia and the People’s Republic of China – have the power to veto resolutions. This makes the permanent members of the Security Council – known as the P5 – the governing elite of the UN.

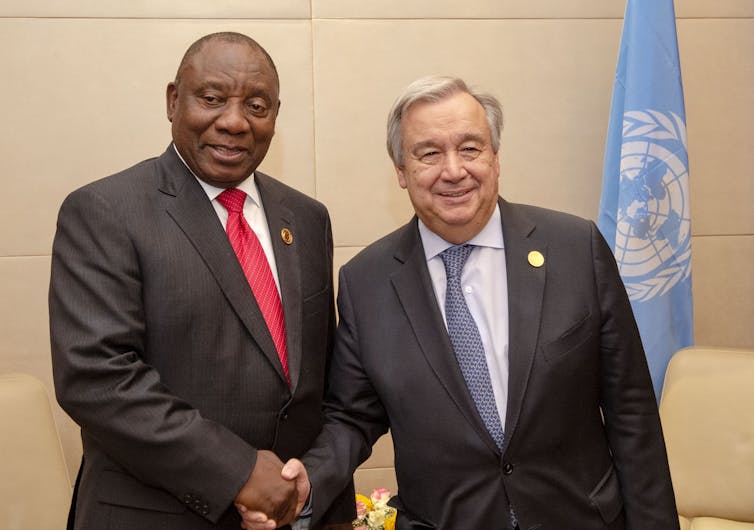

The day-to-day work of the UN is done by the Secretariat, which is headed by the Secretary-General – curently Antonio Guterres – who is the de facto chief executive officer of the UN.

Election to the Security Council is prestigious for member states because it gives them a seat at the highest table of global decision-making.

What’s a stake

South Africa’s re-election to the Security Council under President Cyril Ramaphosa raised hopes of a return to the foreign policy of President Nelson Mandela and a stronger commitment to human rights. Though admirable, the fact is that the world has changed dramatically since the Mandela presidency which ended in 1999.

Pretoria needs to update its approach to the Security Council to suit the pressures of a changing world order. This is illustrated by a number of events that have contributed to a decline in the currency of democracy and set back debates about global human rights.

These include the presidency of Donald Trump which has led to the US all but abandoning its role as guarantor of the liberal international world order. In addition, China is entrenching its position as the new superpower while Vladimir Putin’s Russia has put great power rivalry back on the international agenda.

The shifts in global power dynamics are starkly shown by the fractures in Security Council. In 2018, there were fewer consensus resolutions passed and an increased use of the veto. This trend appears to be continuing in 2019. Earlier this year two draft resolutions on the situation in Venezuela failed while so far six resolutions have passed without consensus.

This matters because for 20 years after the end of the Cold War, there was a shift towards consensus decision-making in the Council. The drafters and supporters of a resolution tried to get broad agreement on the text before submitting it for discussion. Consensus decisions gave the Security Council the appearance of legitimacy because the individual five permanent members cooperated with the majority instead of using their structural power to enforce their particular perspective or interests.

The increased use of the veto and failure to get consensus decisions reflects the return of superpower rivalry and division in the Council since the 2011 NATO intervention in Libya and the ongoing stalemate in addressing the intractable war in Syria.

But tensions among the permanent members provide an opportunity for the ten elected non-permanent elected members to exert greater influence over Council operations.

The highlight of South Africa’s tenure will be in October 2019 when it holds the rotating presidency of the Security Council. This is one of the highlights for elected Security Council members. They generally use their presidencies to present themes that are not officially on the Council agenda or to keep issues that would otherwise be neglected on the agenda.

South Africa’s Permanent Representative Jerry Matjila has been in the position for three years and has built good relationships with his counterparts. He appears to be able to balance South Africa’s interests and interaction with partners from the global north and the global south.

Difficult decisions

As in its previous two terms, Pretoria’s focus for its tenure in the Security Council is the maintenance of peace and security in Africa. This was tested earlier this year when election results in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) were contested.

Western members of the Security Council, especially Belgium and France, unsuccessfully sought South Africa’s support to take a strong position against any possible fraud in the results. South Africa refused, and aligned itself with the Southern Africa Development Community that favoured the formation of a DRC government based on the results released by the electoral authorities.

China and Russia were aligned with South Africa in viewing this as an internal and sovereign issue that required no further involvement from the Security Council. In the event, Felix Tshisekedi was sworn in as President on 24 January 2019 and was recognised as the legitimate head of state by Council members.

Aside from challenges within Africa, the biggest controversy of South Africa’s tenure so far was the vote on two competing draft resolutions – one sponsored by Russia the other by the US – in response to the political situation in Venezuela. South Africa voted against a US-sponsored draft that called into question President Nicolás Maduro’s election in a poll in May last year. The draft failed because of vetoes from China and Russia.

South Africa’s voting decisions on the issue were consistent with its stated foreign policy. Pretoria has long opposed regime change and international intervention except in very particular circumstances. The debacle over its vote for resolution 1973 in March 2011 authorising military intervention in Libya still leaves an embarrassing aftertaste.

So far, South Africa has managed its tenure in the Security Council by taking cautious and calculated decisions. The appointment of a new minister, Naledi Pandor, to the international relations ministry bodes well for the rest of South Africa’s term. She is a seasoned politician with the necessary gravitas to restore respect in South Africa’s foreign policy. She also has the trust of President Cyril Ramaphosa, which is important for giving the Department of International Relations and Cooperation the authority to make tough decisions on the Council.

Sithembile Mbete, Lecturer, University of Pretoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.