Nick Robinson, University of Leeds

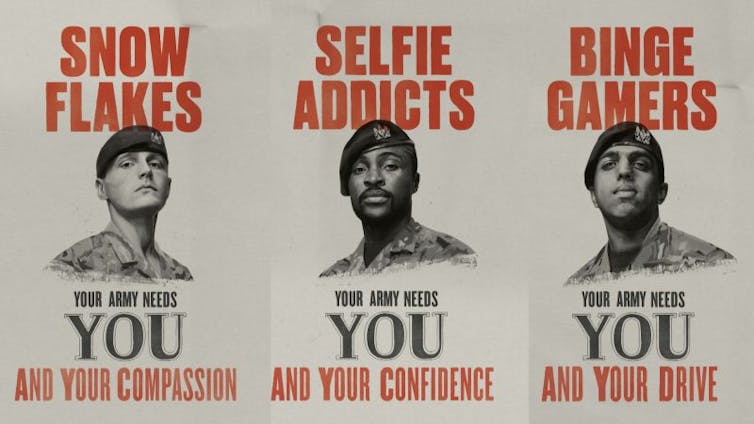

The decision by the British army to place a glossy supplement inside the plastic wrap for the February 2019 issues of both the official Xbox and PlayStation magazines in the UK has created an overwhelmingly hostile reaction. Critics accuse the military of inappropriately targeting minors through the association of the “serious business” of the military with the “trivial nature” of gaming.

But such criticisms overlook the longstanding relationship between entertainment and military recruitment.

The US military, for example, developed the game “America’s Army” in 2002 which has since been played by more than 15m people and evaluated as one of their most effective recruitment tools. In the US, controversy over this game has centred on the decision to remove blood and gore from the gameplay, enabling it to be played by younger teenagers. The UK military has also made use of game-based recruitment for nearly a decade, with interactive social media campaigns and online campaigns designed to appeal to would-be recruits.

Read more: How the US military is using ‚violent, chaotic, beautiful‘ video games to train soldiers

It’s also worth noting that the release of the 1986 film Top Gun was followed by a massive boost in applications from budding US navy pilots.

Military-style video games are becoming ever more popular – the bestselling Call of Duty series, for example, has achieved combined sales of more than 250m copies and revenues of over US$15billion (£12 billion). While these games are regulated by national ratings agencies in almost all major gaming markets (and given adult or 17+ ratings), research suggests that huge numbers of underage gamers frequently access mature content.

In an attempt to restrict access to the young, the British army’s “gamer supplement” is sealed in a magazine which you have to be 18 to buy. So, given that this supplement is, theoretically at least, only accessible to adults why the worry?

Underage gaming

Despite national regulation, across the UK and elsewhere, large numbers of underage gamers play adult-rated games. National law in the UK makes it illegal for any retailer to sell a game rated 12 and above to anyone who is underage. While there is no legally binding policy in the US, according to a recent Federal Trade Commission undercover shopper survey, only 13% of underage teenage shoppers were able to buy M-rated video games. The survey found that of all age-related media – including movie tickets and CDs and DVDs with parental warnings – it was access to video and computer games that were most effectively restricted to minors. But despite this, research consistently shows that vast numbers of children continue to play mature-rated military games.

Given this – and widespread concerns about the vulnerability of youngsters to desensitisation and the allure of heroic military narratives – important ethical questions are raised by the British military’s ploy. Assuming they are fully aware that children will read a supplement which celebrates the synergy between gaming and military life (even though, in theory, they cannot get access to it) perhaps they should not have produced it at all.

The recruitment dilemma

The answer may not be as simple as it appears. Armed forces throughout the Western world face major recruitment challenges and application numbers continue to fall. Indeed, an inquiry has also just been launched in the UK to investigate why increasing numbers are quitting the military. Consequently, there is a clear rationale for militaries to do all they can to address these problems. Perhaps the key question – in the UK at least – is whether it is appropriate that the legal age of recruitment remains 16.

Given that games are so frequently played by under-18s, that the supplement is likely to be read by under-18s, and that it makes explicit reference to the steps potential recruits would need to take to join at 16, those who accuse the military of inappropriately targeting minors are right to be concerned. Fundamentally, this is not a game – instead it highlights the need to ask whether the UK military should still be targeting children at all.

Nick Robinson, Associate Professor in Politics, University of Leeds

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.