The sound of the water flowing from the fountain that now stands towering in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall creates a calming softness in contrast to the cold, hard concrete floor on which I sit trying to take in the 13-metre-tall monument before me.

The sculpture is both calming and distressing: presenting painful histories of the black Atlantic slave trade in the “delightful family-friendly setting” of a public art museum. The characters of Venus, The Captain and Queen Vicky stand or sit around the monument’s plinth. A mother directs her young son’s gaze up to the water gently pouring down from above them. She does not point to the trunk of a tree planted on the side of the monument where these characters do not rest. It is not so pretty, not so easy to delight in. It is a tree without life: no branches, no leaves, only ghostly bodies hanging from an empty noose.

Painted on the Turbine Hall wall, the text for Kara Walker’s sculpture, Fons Americanus, calls visitors to “Gasp Plaintively, Sigh Mournfully and Gaze Knowingly” at her recasting of the Victoria Memorial which stands outside Buckingham Palace. This monument featured in my own undergraduate dissertation. In that, I explored representations of black British women’s history in London’s urban landscape by walking the city.

The only representations I found around the city placed imaginary women of “Africa” at the base of columns which celebrated Britain’s empire. I don’t think I particularly noticed then the absence of references to the slave trade. I focused on bringing to light the presence of the black Victorians who were nowhere to be found in the memorial fabric of the city in which I walked and this has remained the focus my research ever since.

Tate curator, Clara Kim, hopes that the work will stimulate a debate around the representation of difficult British histories in the urban landscape. It is a conversation that is sorely needed, but has been called for for some time.

In 1807, the Act for the Abolition of the British Trade in Slaves from any part of the coast or countries of Africa was enacted. As the bicentenary approached in 2007, discussions about how this bicentenary would and should be commemorated – rather than celebrated – heightened.

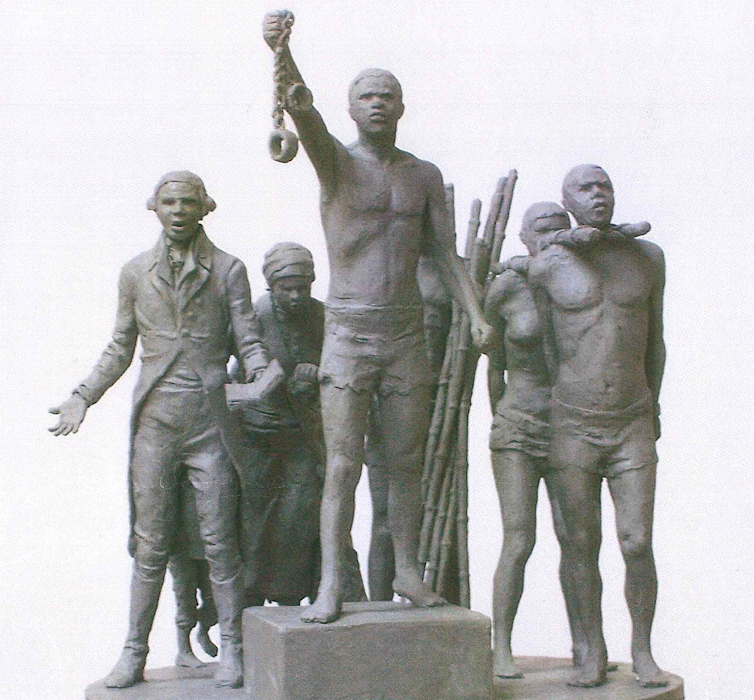

Memorial 2007 launched a campaign to memorialise not the white parliamentary abolitionists, but the Africans who were victims of and fought against the institutions of British slavery. The intention was for the sculpture, chosen by public competition, to be unveiled during the bicentenary year in 2007. Twelve years on, Walker’s intervention at Tate Modern is a stark reminder that no such memorial on a national scale has yet found a place in the capital.

Chaired by Oku Ekpenyon, Memorial 2007 has been campaigning since 2002 to raise funds to complete its mission, but that campaign is now nearly out of time. The group have secured planning permission for a space in the Rose Gardens in Hyde Park, but this expires in less than a month, on November 7, 2019.

Every prime minister since the group formed has been asked to support the memorial, but no funds have been forthcoming. Although Boris Johnson, then Mayor of London, hosted an unveiling of a statuette of the memorial sculpture at City Hall, letters to Number 10 since he became prime minister have been met with silence. A petition to ask the government to fund the memorial before the deadline has been gaining momentum.

The state’s failure to acknowledge the pain and suffering of the victims of the British transatlantic slave trade through memorialisation is reflective of its failure to acknowledge the legacies of enslavement in contemporary Britain; its legacies of financial and social capital for those who benefited from it and the ongoing marginalisation of the descendants of those who were enslaved, as the recent Windrush Scandal painfully exposed. For Ekpenyon, the campaign to bring a memorial into being has been an exhausting 17 years of frustration, disappointment, anger and sadness.

When I visited Tate’s Turbine Hall, visitors were walking around Walker’s fountain, craning their necks skyward to its peak, angling to get as much as possible of it in frame for a picture. I stood alone looking into the stricken face that appears from the sculptured folds of the Shell Grotto at the hall’s entrance. Here, the flowing water is a silent, steady stream of tears.

Caroline Bressey, Reader in Historical Geography, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.