Craig Anthony Johnson, University of Guelph and Iftekharul Haque, University of Ottawa

Over the last month, the Canadian government has been embroiled in a political controversy, involving allegations that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau put undue pressure on Jody Wilson-Raybould, the country’s former justice minister and attorney general, to negotiate a deferred prosecution agreement with Québec engineering giant SNC-Lavalin Group.

In Canada, such agreements — which have already been adopted in the United Kingdom and the United States — empower the Director of Public Prosecutions to negotiate reduced sentences with companies whose officials have been accused of engaging in criminal acts.

In the midst of the saga, the prime minister’s principal secretary and two senior members of his government – Wilson-Raybould and Jane Philpott – have resigned from cabinet, and the SNC-Lavalin affair shows no signs of abating.

Read more: Saying no to power: The resignations of women cabinet members

So far, the vast majority of political and media commentary has focused on the appropriateness of the actions of the Prime Minister’s Office and the economic impact of jeopardizing 9,000 jobs in Canada should SNC-Lavalin face criminal prosecution.

These aren’t inconsequential matters. But they are part of a much wider conversation that needs to be had about the economic and political consequences of allowing and condoning corrupt business practices outside of Canada.

Guarding against corruption

Promoting and protecting jobs in Canada is part of any government’s political mandate. But so too is the responsibility of ensuring that Canadian businesses are not creating further costs for countries whose governments and populations are least able to bear the burden of endemic corruption.

Read more: SNC-Lavalin: Canada’s anti-foreign bribery laws did their job

What are some of these burdens?

First, bribery inflates the costs of undertaking infrastructure projects that have real and significant benefits for poor people in the developing world.

Take for instance the case of Bangladesh, a country in which SNC-Lavalin was accused of bribing officials in the construction of the Padma Bridge, a US$1.2 billion project that was being funded by the World Bank.

According to a recent World Bank study, road construction in Bangladesh is up to 10 times more expensive than it is in India and China, reflecting the costs of high-level corruption. Although the charges against SNC-Lavalin in Canada were ultimately dropped, the company’s international subsidiary — SNC-Lavalin Inc. — was barred from bidding on all future World Bank infrastructure projects for a period of 10 years.

Second, bribery narrows the pool of possible applicants, reducing the quality of services and benefits. Tendering large infrastructure projects is a complex process, involving many officials, but shrinking the pool makes it difficult to ensure that contractors are meeting their targets and deadlines.

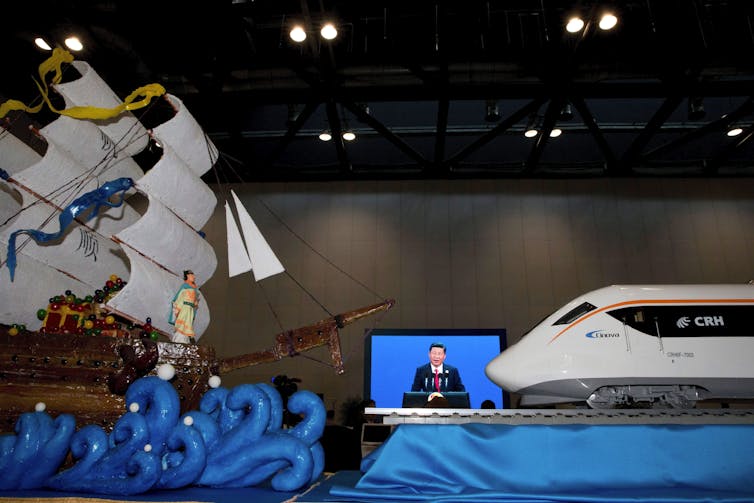

China’s Belt and Road Initiative, aimed at building construction projects in more than 60 countries to connect Asia, Africa and Europe, has widened the field.

But its approach entails using debt to secure infrastructure contracts, producing work that has been described as sub-standard and incomplete.

Third, bribery puts money in the hands of a small and powerful elite, further undermining the prospects for democratic governance that are so strongly associated with improved living standards and economic performance.

An ethical foreign policy?

In the case of Libya, SNC-Lavalin stands accused of paying $48 million in bribes to public officials, including Saadi Gadhafi, the son of Libya’s former dictator, for travel, hotels and escorts.

Beyond the obvious legal and ethical implications of this particular case, a major problem with corruption of this kind is that it hollows out the foundations for democratic governance that are absolutely essential for achieving long-term sustainable development.

Defenders argue that paying bribes is part of doing business, but doing so also undermines critical public institutions, such as the judiciary, the executive and the civil service. It diverts public and private investment away from employment and infrastructure (as well as education and health care) into the assets and foreign bank accounts of political elites.

When the Liberals came to power in 2015, they promised to “refocus Canada’s development assistance on helping the poorest and most vulnerable, and supporting fragile states.”

With the case of SNC-Lavalin, the government now finds itself in the unenviable position of having to choose between supporting a company that has been accused of engaging in widespread corruption or sticking to the humanitarian principles that were part of its original mandate.

It’s true the company employs more than 50,000 people in 50 countries around the world, but it must also be noted that SNC-Lavalin’s actions —and those of the Prime Minister’s Office — have implications for people living outside of Canada, including those in some of the world’s poorest and most unstable countries.

Although they don’t vote in Canadian elections, and they probably don’t hold shares in SNC-Lavalin, they are stakeholders too, and their interests should be part of the conversation. Such are the foundations of an ethical foreign policy.

Craig Anthony Johnson, Professor and Director, Guelph Institute of Development Studies, University of Guelph and Iftekharul Haque, Ph.D. candidate, University of Ottawa

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.