D.T. Cochrane, York University, Canada

Indigenous jurisdiction is at the centre of the dispute over the Coastal GasLink pipeline. The same is true of the Trans Mountain expansion. In both cases, the corporations involved have misunderstood or misrepresented the risks associated with jurisdictional uncertainty.

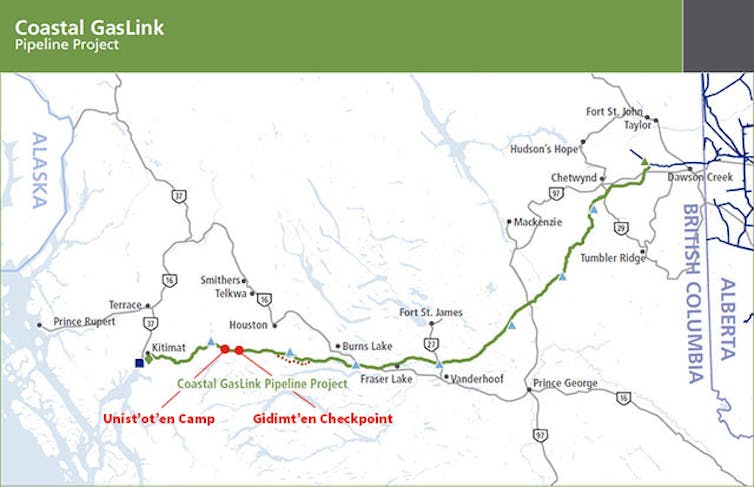

The Coastal GasLink pipeline is part of the massive LNG Canada project. If built, the pipeline would ship fracked methane from an area around the northern Alberta-British Columbia border to an export facility in Kitimat, B.C. Coastal GasLink is to be constructed, owned and operated by TransCanada Corp.

The planned route passes through traditional Wet’suwet’en territory. The hereditary chiefs of the Wet’suwet’en reject the pipeline. Two clans, the Unist’ot’en and the Gidimt’en, have erected checkpoints to protect their lands.

Visitors have to obtain permission to enter this territory. Workers and representatives of Coastal GasLink were denied access.

The company sought an injunction, which was awarded in December. It was at one of these checkpoints that the RCMP, enforcing the injunction, confronted and arrested 14 Wet’suwet’en land defenders.

Ignorance or obfuscation?

After the arrests, Coastal GasLink president Rick Gateman said in a statement: “Our fully approved and permitted project has the support of the communities and all 20 elected Indigenous bands along the route, as well as many hereditary chiefs.”

The statement echoes TransCanada’s refrain about Indigenous jurisdiction and reveals either ignorance or obfuscation.

There are meaningful differences between band leadership and traditional leadership, as well as between Indigenous nations. Those differences have consequences for the viability of TransCanada’s project. From a risk management perspective, either ignorance or obfuscation is a huge failure.

Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs have authority

The hereditary chiefs of the Wet’suwet’en unanimously reject the pipeline. The opinions of chiefs from other nations pertain to their lands, not Wet’suwet’en lands.

The differences between band leadership and traditional leadership have jurisdictional consequences. The authority of the bands comes from Canada’s Indian Act, which many Indigenous people reject. Conversely, the authority of the Wet’suwet’en hereditary leadership predates European contact.

Band leadership has authority over reserve lands. Conversely, traditional leadership has authority over a nation’s traditional territory, which subsumes and exceeds reserve lands. That authority has been acknowledged and upheld by the Supreme Court of Canada.

Court recognizes Indigenous rights & title

Delgamuukw v. British Columbia is one of the most important Supreme Court of Canada decisions regarding Indigenous rights. The justices ruled the Wet’suwet’en and the Gitksan demonstrated land title right to their respective territories. In a later ruling, Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia, the court recognized that the nation — not the band — holds title to their lands.

Although the Delgamuukw decision recognized Wet’suwet’en rights and title, the Supreme Court did not rule on jurisdiction, saying a new court case would be required. Ryerson University Prof. Shiri Pasternak notes the ruling presumes underlying Crown title and “shifts legislative authority over resources away from Indigenous peoples.” The justices in the case identified “the general economic development of the interior of British Columbia” as a reason Indigenous title could be infringed.

Indigenous jurisdiction protected by UN

Jennifer Wickham, a member of the Wet’suwet’en nation, addressed the shortcomings of the Delgamuukw ruling and the entire court process: “Even when we follow their Western law, it doesn’t do us any good.” Such sentiments express why the Wet’suwet’en, and other Indigenous nations, are turning to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), as well as land defence strategies.

The late Secwepemc leader, Arthur Manuel, observed that Canada’s longstanding opposition to UNDRIP was because the declaration enshrined self-determination. According to Manuel, self-determination would give Indigenous people economic control of their lands, which he said Canadian governments could not abide.

During the 2015 federal election campaign, the Liberals promised to implement UNDRIP. After winning the election, they hedged their promise. Justice Minister Jody Wilson-Raybould said adopting the international framework into Canadian law is “unworkable.”

Wilson-Raybould backtracked after intense criticism.

The Liberals then supported a New Democrat-sponsored bill for full adaptation of Canadian laws to UNDRIP. However, Wilson-Raybould hedged again, saying more work would be needed. She has since been shuffled out of her cabinet position to Veteran Affairs.

Canada is making uncertainty worse

Governments and corporations consult with Indian Act bands to generate support for resource projects. This confuses the source and scope of Indigenous rights and title. It also provokes land defences like in Wet’suwet’en. Ultimately, it increases uncertainty.

The Wet’suwet’en have allowed Coastal GasLink access to their lands. But they insist that this is “a waste of their time and resources as they will not be building a pipeline in our traditional territory.”

If TransCanada sincerely believes it has the consent of the appropriate Indigenous leaders, it betrays a profound misunderstanding of Indigenous rights. It is worse if the company knows it does not have the proper consent. Either way, investors should be concerned.

Indigenous people will continue to use diverse means to assert and defend their jurisdiction. Corporations seeking to operate on Indigenous territory must prove they understand the meaning of Indigenous jurisdiction. Until they do, investors should seek their returns elsewhere.

D.T. Cochrane, Lecturer in Business and Society, York University, Canada

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.