Greg Beckett, Western University

Haiti’s public utility company just announced it’s reducing output again. The move comes after a series of blackouts throughout the country, some lasting weeks. The power outages are the result of a weeks-long fuel shortage that has led to fuel rationing and gas station closures as reserves run dry.

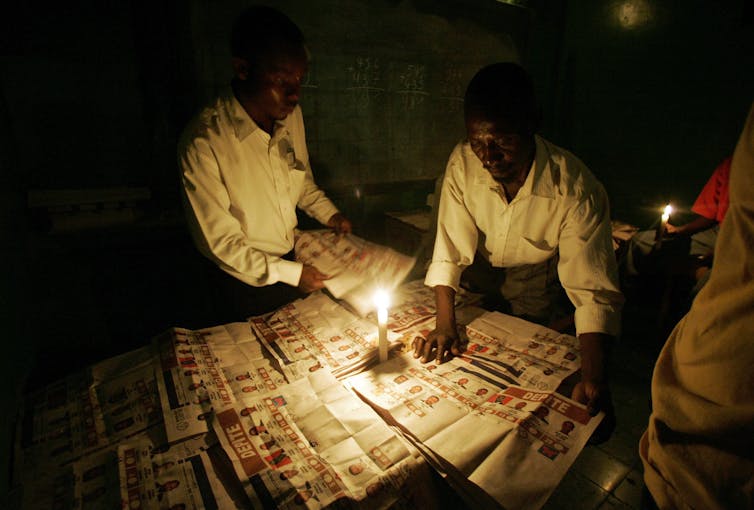

Haiti is dependent on fuel imports, and the national electrical grid is small and inefficient. Haiti’s already weak infrastructure has been damaged by a string of natural disasters. Yet, for many Haitians, blackouts are not just the result of the country’s vulnerability; they are also a symbol of political crisis.

Blackouts routine in Haiti

Blackouts are expected occurrences in Haiti. When they inevitably happen, talk quickly turns to the government’s inability to provide basic services.

Most electricity comes from the state-run provider, Electricité d’Haiti (EDH), which is seen as being poorly managed and corrupt. When the lights go out, as they invariably do, the problem of the lack of services is made abundantly visible.

Electricity is a charged political issue in Haiti. Only about 25 per cent of the population has access to electricity, and those who do rarely have it all day, every day. Private businesses and wealthy families rely on diesel generators for their shops and homes. Poor Haitians use wood, charcoal or kerosene.

Most governments have sought to expand access to energy sources and to subsidize their cost. Most recently, President Jovenel Moïse pledged to bring “24 hours around the clock” electrical service to Haiti within two years. Instead, he presides over a country wracked by chronic energy shortages.

The politics of fuel

The Caribbean has some of the highest utility rates in the world. In 2005, Venezuela launched Petrocaribe, an oil alliance designed to alleviate fuel costs and promote economic co-operation.

Under the plan, member states paid only 40 to 70 per cent of the price of fuel imports. The remainder was deferred, to be repaid over 25 years with an annual one per cent interest rate. Funds from fuel sales were to be spent on social development programs.

The current fuel shortage in Haiti is part of a larger story about the fallout from the crisis in Venezuela. In 2017, the Haitian Senate released a report claiming that $1.7 billion from the Petrocaribe fund had been lost or stolen and that the program had racked up US$2 billion in debt.

A just-released audit conducted by Haiti’s Superior Court of Accounts and Administrative Disputes confirmed these claims and added that many of the development projects sponsored by Petrocaribe funds were never finished or never existed.

The Petrocaribe scandal and the energy crisis have both given rise to renewed calls to privatize Haiti’s energy sector. Haiti has been forced to end its involvement in Petrocaribe; the country now buys its fuel from American providers, in U.S. dollars, continuing a long-standing program of American energy imperialism in the region.

If the new fuel prices imposed by the International Monetary Fund last year are any indication, privatization and liberalization of the energy sector in Haiti will make life more expensive for most people and make the country more dependent and more indebted to foreign powers.

It’s a situation reminiscent of Puerto Rico, where debt and disaster have been leveraged to push through a series of neoliberal structural adjustment programs in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria.

Losing power

In Haitian Kreyòl, the word for power outage is blakawout. It refers to the loss of electrical power but, like its English equivalent, can also be used to talk about a bodily condition.

In Port-au-Prince, it is common to hear people talk about blackouts in a number of ways.

Where we might say in English that a person can suffer a blackout, meaning a loss of consciousness, Haitians might say they are “living in a blackout,” a phrase that speaks to a more generalized loss of physical and social energy.

Sometimes they refer to power outages to complain about the government and the lack of essential services. Other times blackouts provoke memories of repression by the Haitian military and paramilitary forces, who would often cut power to neighbourhoods before conducting violent raids.

Sometimes people say that when there is a blackout they simply “can’t do anything” at all, as if the lack of light and electrical power is only the visible symptom of a more general condition — the loss of agency.

For many Haitians, blackouts do not just signal a political crisis — they also symbolize feelings of their loss of political power. In that sense, blackouts are not just the result of a weak government. They are a symptom of a deeper crisis of sovereignty as the Haitian people continue to struggle, still, for democracy, autonomy and self-determination.

Greg Beckett, Assistant Professor of Anthropology, Western University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.