Janusz Paweska, National Institute for Communicable Diseases

The last patient receiving treatment for Ebola was recently discharged from an Ebola Treatment Centre in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

The current outbreak of Ebola emerged in the northeastern part of the country in August 2018. It spread across three provinces, infecting over 3,300 people with a case fatality rate of 65%. A few cases were also reported in Uganda last year. This is the 10th Ebola outbreak in the DRC. It has been the most severe since the first recognised outbreak in the DRC in 1976.

But those managing the outbreak in the DRC aren’t completely letting their guard down – just yet. Forty-six individuals who had come into contact with the last patient are still being monitored. In addition, all Ebola control and response measures are still in place to ensure that any new cases are detected quickly and treated.

The incubation period for Ebola is 21 days. This is the period from exposure to the development of clinical symptoms. The outbreak can only be considered over when no new cases are diagnosed 42 days (double the incubation period) after the last reported case has tested negative. The last case of Ebola in the DRC was recorded on the 17th of February.

A great number of very useful lessons have come out of the trauma of the past 19 months. In my view there were seven key interventions and developments. These included the development of safe and efficient Ebola vaccines. So too was improving diagnostics that can be used easily in less resourced and remote areas. And, importantly, learning that control of a disease outbreak like Ebola is impossible without community trust and engagement.

Bringing the outbreak under control

There were a number of factors which eventually led to controlling the outbreak. These included:

Diagnostic technology: The implementation of new and relatively easy-to-use diagnostic technology such as the commercial GeneXpert Ebola assay was a game changer. This technology allowed for faster results and the tests could be done by locally trained staff.

A rapid diagnosis helps to prevent the spread of the disease among family members, communities and at hospitals. The faster a case can be identified, the faster it can be taken care of in terms of isolation and treatment. This also allows for contacts to be vaccinated in time.

Experimental vaccines: The development of a number of experimental vaccines were key. They saved the lives of many people, prevented wider spread and assisted in rebuilding trust in public health measures.

Research at the scene: Locating research on the scene of the outbreak prioritised the experimental testing of various treatments and vaccines to aid science-based responses.

Follow-up care for survivors: Offering survivors a comprehensive programme of follow-up medical care to counter serious post-infection conditions, for example blindness, and providing psychological support.

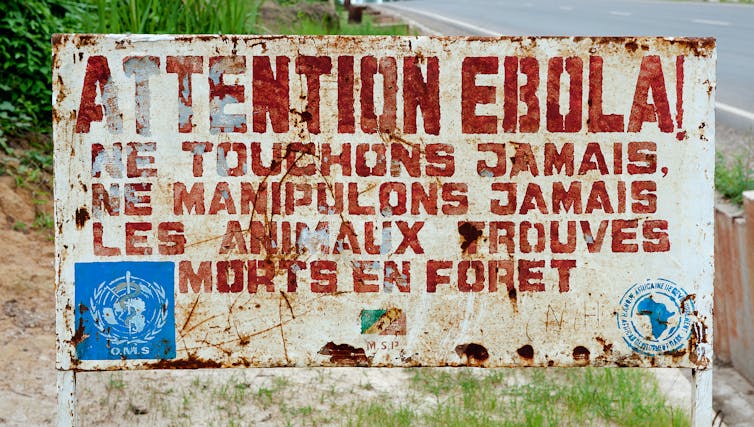

Engaging people: Innovative medical technologies (vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics) are not enough to prevent and contain epidemics. What’s needed is the inclusion of social science as an important component of outbreak management. What I mean by this is that communities need to be engaged and empowered as primary partners in preparing and responding to an outbreak. But gaining their trust involves understanding their perception of control measures. For example, why don’t local people trust national governments and the health system? Why don’t they accept health interventions, including vaccination? Why don’t they adopt preventive behaviours, including safe burials? Why do they perceive foreign medical interventions as bio-terrorist experiments at their expense? Social scientists are best able to understand these dynamics, which is why they should be involved.

Stability: Stabilisation of political unrest in recent months made access to medical care easier and allowed all the well-known strategies for controlling Ebola to be implemented. This included contact tracing, safe burial practices, isolation treatment, surveillance, lab testing, community engagement, as well as public health education.

Massive international support. As with other major Ebola outbreaks in Africa, this one could not have been brought to ground zero and controlled without massive international support. On the people front, this included medical staff, epidemiologists, infection prevention control and risk communication and community engagement specialists, logisticians, diagnosticians and salaries for local staff. It also included medical and diagnostic supplies and equipment, field-operated hospitals, medicines and vaccines.

Those who contributed to these long lists included the World Health Organisation’s Health Emergency Programme and its Global Outbreak and Response Network, Doctors Without Borders, US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, UNICEF, Red Cross, World Bank, individual countries and government as well as public health agencies, institutions and universities.

What next

On the longer term horizon, strengthening Africa’s health systems and building citizen trust will be pivotal to responding to increasing numbers of emerging infectious diseases. African health systems can’t depend on donor generosity alone. They also require economic and political commitment from national leaders and the communities they govern.

African scientists also need more support if the continent is going to secure and develop long-term and effective preparedness and response strategies to cope with epidemic prone infectious diseases. They need should have better training opportunities as well as great involvement in scientific programmes. They also need to be provided with access to adequate bio-containment facilities – secure facilities to prevent the accidental release of pathogens during research – to improve regional counter measures against emerging and re-emerging dangerous pathogens.

On these points, there is a lot to be done.

Janusz Paweska, Head of the Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Diseases, National Institute for Communicable Diseases

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.