Mats Fridlund, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

What is it that allows someone to be labelled as a terrorist? Recent acts of spectacular violence, such as the mail bombs sent to American anti-Trump critics, or the mass killings by Canadian “incel” misogynist Alek Minassian, demonstrate a widespread reluctance among media outlets, politicians and authorities to label some acts of ideologically motivated violence as “terrorism”. Such hesitations might give the faulty impression that “terrorism” is reserved purely for anti-Western or Islamist political violence. That is a wrong and dangerous conception.

There is no question that terrorism is neither an exclusively Islamist nor a new or recent phenomena. Terrorism has many and diverse ideological motivations and a long history. Indeed, it could even be claimed that modern terrorism is a product of Western modernity.

Most terrorism experts would probably agree that terrorism is an ideologically neutral tactic, used to achieve political change, and in play since prehistoric times. It is neutral, although not necessarily acceptable, in that it has been used by militants embracing most political ideologies – except for pacifism – and by authoritarian as well as liberal states such as Great Britain, France and the USA.

Although no universally accepted definition exists, there is agreement about its main elements. Terrorism is the threat or use of violence, it is politically or ideologically motivated and the violence is used to communicate a message of political change and intimidation to individuals or groups beyond its immediate victims. In short, terrorism is best understood as violence used as a form of political communication.

Although modern terrorism followed the emergence of modern mass politics and mass media, terrorist violence has probably been used as a political tactic since time immemorial. The Jewish Zealots and the Islamic Assassins – title-characters of the Assassin’s Creed video games – were ancient terrorists. They used violence to communicate messages of freedom from opposition and resistance to submission.

From states to individuals

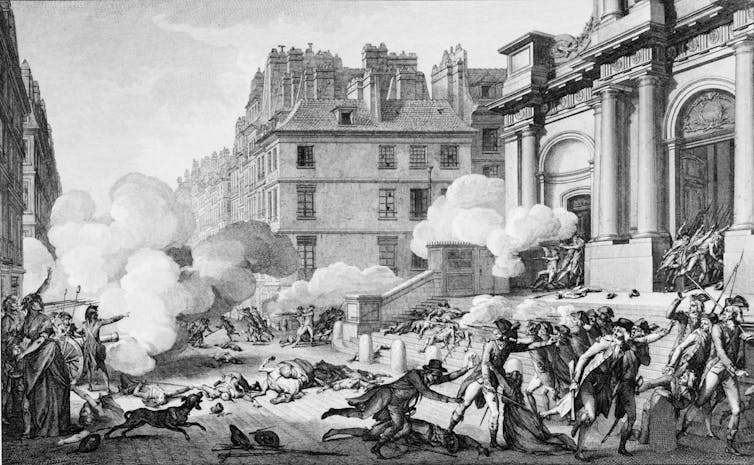

Terrorism’s modern meaning and use to label an intentional political tactic came with the French Revolution. During The Terror, Robespierre described it as a virtuous form of violence, to be used by the new revolutionary democratic state against its domestic enemies.

Following this, the labels of terrorism and terrorists were used by 19th century newspapers to describe intimidation and violence by states against their subjects, such as “the terrorism practiced by the police” in Russia and the “oppressive system of military terrorism” in Poland.

Modern terrorism, which implies the systematic use of violence against the state, rather than by it, emerged in Europe in the 1870s. The person generally recognised as the first terrorist was the 26-year-old social revolutionary Vera Zasulich, who shot the Governor of St Petersburg in 1878 to protest the Russian state’s repression of domestic political protest.

In its agitation for a social revolution in Russia in line with the French Revolution, the Russian revolutionary movement until this point only used non-violent “propaganda by the word”. Zasulich’s shot broke the taboo against using violence to communicate political messages. Its worldwide publicity showed political activists and groups a new form of political protest, a spectacular and frightening “propaganda by the deed”.

Similar assassination attempts were first used against European governments and politicians, but by the early 1900s the new political tactic had spread to all the world’s inhabited continents, known in India as “the Russian method” and in China as “assassinationism”.

Products of Western modernity

The new violent political practice was soon institutionalised with the emergence of organised terrorist groups. First came Narodnaya Volya (The People’s Will), a group of Russian social revolutionaries and self-proclaimed terrorists, who in 1881 succeeded in assassinating Tsar Alexander II with a dynamite bomb.

The Russian terrorists’ struggle against the repressive Russian state was to some degree accepted and even admired by several Western observers. Mark Twain, for example, declared that if the Russian “government cannot be overthrown otherwise than by dynamite, then thank God for dynamite!”

These first modern terrorists were like present day terrorists in that their actions were made possible through the use of industrial products of Western modernity. Spectacular violence was executed using commercial technologies such as industrially manufactured revolvers and Alfred Nobel’s science-based dynamite invention. Terrifying political messages were spread internationally through news articles transmitted by transatlantic telegraph cables and printed by commercial mass media companies on steam-powered printing presses.

Also, these first examples of people being labelled “terrorists” were almost exclusively reserved for acts of non-Western terrorism. When terrorist tactics were used against governments and civilians in Western Europe or the USA – by Fenians and anarchists or anti-colonial separatists in British India, for example – terrorism was generally not mentioned. Instead, such violence was more often described in terms of outrage or assassination.

This is despite the fact that these groups used the same terrorist tactics and technologies as the Russian terrorists. The new terminology was apparently reserved for the Russian revolutionary cause. It was only after World War I that these other forms of terrorism in and against Western governments started to more generally be labelled as terrorism.

This is the genuine starting point for the more widely recognised form of violent political communication that we today know and describe as terrorism.

Mats Fridlund, Visiting Scholar, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.