Cynthia Levine-Rasky, Queen’s University, Ontario

When white supremacists rallied in Charlottesville, Va., in August 2017, it woke the world up to the mobilization of extremist groups in our North American cities. With the recent announcement that the white supremacist who organized the Charlottesville rally is planning to mark the anniversary with an event in Washington, D.C., it becomes undeniable.

What ideas fuel such groups? A clue lies in the Charlottesville cry of “you will not replace us,” which morphed into “Jews will not replace us.”

The rallies are an indication of a fear of an imminent “white genocide,” a propaganda term used by white supremacists to indicate their beliefs that the “white race” is dying. This fear is so central that it’s inscribed in their infamous slogan known as “the fourteen words”: “We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children.”

“White genocide?”

As it turns out, the idea is not original. The current ideas of the white nationalist movement are old ones full of myths and unscientific, obsolete “research.”

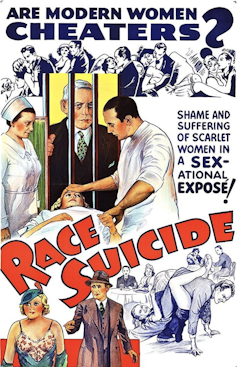

The idea of white genocide comes from the concept of “race suicide” first articulated by intellectuals and politicians well over 100 years ago.

Race suicide

Talk of “race suicide,” the idea that the white population could die out, was so popular in its day that it shaped laws and policies in both the United States and Canada, including: Immigration law, eugenics programs and the prohibition of abortion . Support for these initiatives were mainstream and expressed by white folks from all social classes and political positions.

Today, that discourse has shifted from mainstream to extremism as contemporary white supremacist groups galvanize members around their trumped-up panic about their eventual demise.

Believing their dominance as a white “race” is threatened, along with their unearned entitlements and conferred dominance, extremist groups promote violence to achieve their desired end — a fictive nation of whiteness.

Their targets are not only racial, ethnic and religious minorities, but also sexual minorities and women. Why? Because power is not restricted to whiteness; it is accomplished intersectionally. In other words, whiteness wields maximum power when it intersects with masculinity and heteronormativity.

Scientific racism

“Race suicide” can be traced to the scientific racism of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A popular literature, it flourished at that time, and was promoted by political leaders and the intellectual elite.

One contributor was Lothrop Stoddard, whose 1920 book, The Rising Tide of Color Against White World Supremacy was the most inflammatory in a line of such books. Stoddard built on his mentor Madison Grant’s 1916 book, The Passing of the Great Race, or the Racial Basis of European History, which in turn was built on his friend William Z. Ripley’s 1899 book, The Races of Europe: A Sociological Study. With little to no references, research or documentation to support their claims, these writers asserted the inherent superiority of the “Nordic” group of Europeans.

But Stoddard went a step further. He wrote that Nordic superiority needed protection from more numerous, inferior traits of other races. He reasoned that Nordic superiority was “genetically recessive” and therefore unstable and in need of political intervention to ensure the segregation of groups.

In his introduction to Stoddard’s book, Grant wrote:

“(if) the white man were to share his blood with, or entrust his ideals to, brown, yellow, black or red men…This is suicide pure and simple, and the first victim of this amazing folly will be the white man himself.”

Francis Amasa Walker, president of Michigan Institute of Technology from 1881 to 1897, and the first president of the American Economic Association, published the first comprehensive statistical case that documented a discrepancy between the birth rates among newly arrived immigrants and that of “old-stock Americans.”

Walker concluded that “inferior foreign-born groups” would effectively displace the superior “native” population. The latter would not compete with immigrants from the “low-wage races.” These “peasants” from southern Italy, Hungary, Austria and Russia were “beaten men from beaten races.”

Another economist, Edward A. Ross, is attributed with coining the term, “race suicide.” In his 1901 book, Ross wrote that despite the superiority of “native” Anglo-Saxons, “Latins, Slavs, Asiatics, and Hebrews” were better adapted to the conditions of industrial capitalism and thus would outbreed the superior Anglo-Saxon race. “Race suicide” was therefore inevitable, he concluded, because modern urban life promoted the survival of racially inferior immigrant races.

A president and a prime minister

“Race suicide” scares were heard from the highest offices. In the U.S., President Theodore Roosevelt adopted it as a cause. Calling race suicide the “greatest problem of civilization,” he pronounced:

“The New England of the future will belong, and ought to belong, to the descendants of the immigrants of yesterday and today, because the descendants of the Puritans ‘have lacked the courage to live,’ have lacked the conscience which ought to make men and women fulfil the primary law of their being.”

In Canada, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King was in full support of measures to prevent race suicide. He said:

“What physical and mental overstrain, and underpay and underfeeding are doing for the race in occasioning infant mortality, a low birth rate, and race degeneration, in increasing nervous disorders and furthering a general predisposition to disease, is appalling.”

Women were targets too

The targets of campaigns to prevent race suicide were not only new immigrants, but also women.

Fears about the consequences of immigration intersected with fears of women’s sexual freedoms. As early as 1867, Horatio Storer, professor of obstetrics and medical jurisprudence at Berkshire Medical Institution and an anti-abortion activist, asked:

“Shall the West and the South be filled by our own children or by those of aliens? This is a question that our own women must answer; upon their loins depends the future destiny of the nation.”

Fears of race suicide arose from dual sources. One was perceptions of immigrant women’s higher fertility. The other was the reproductive freedom enjoyed by modern urban women. The belief was that too few babies were born to desirable segments of society, and too many were born to the rest.

On this theme in 1917, University of Michigan academic Warren Thompson wrote: “The presence of a large number of unmarried women or women who marry late in life, as in our city population at present, is in itself a proof of race suicide.”

Treatises on the issue implored white women to save the race through stringent adoption of conservative moral standards and the prohibition of abortion.

Current attacks on immigrants

In the absence of an authentic political vision shared among extremists today, race substitutes for belongingness —not to the kind of civic nation-building of the past, but to an imaginary society of white purity.

Then as now, white supremacists lean on the discourse of intellectuals and political leaders to convey legitimacy to their claims.

Then as now, the cry of race suicide inverts the status of victim in which white supremacy is at risk of annihilation.

It is white extremists who insist that they are at risk of annihilation rather than the source of oppression. It is “the Other” that must be controlled through various means, whether sanctioned by the state or not.

Then as now, the perceived risk of “race suicide” is not only to white supremacy, but to the preservation of an entire way of life upon which white supremacy is projected. In other words, they seek to establish a way of life built on a power and a status whose enjoyment is unquestioned.

In response to this risk, white supremacists advocate for a multi-pronged attack against immigrants and other groups.

“Race suicide” turns out not to be about whiteness after all. Then as now, it is about violent power operating intersectionally through race, gender and nativism. The oppression of groups deemed “naturally inferior,” whether they are refugees, sexual minorities or religious minorities, is the organizing principle of white extremist groups who fear that they could be “replaced.”

Cynthia Levine-Rasky, Associate Professor, Department of Sociology, Queen’s University, Ontario

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.