Andrew Edward Tchie, King’s College London

South Sudan’s five-year conflict has killed nearly 400,000 people, created more than 4 million refugees and displaced 1.8 million inside the country.

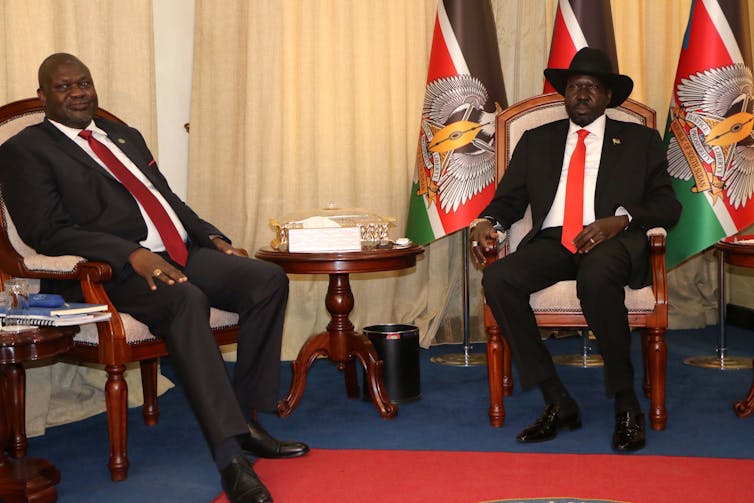

South Sudan should be a country full of hope eight years after gaining independence from Sudan. Instead, it’s now in the grip of a massive humanitarian crisis and recurring conflict. Fighting broke out in 2013 when President Salva Kiir accused then vice president Riek Machar of an attempted coup. Machar was then dismissed from his position.

Further fighting would erupt in Juba in 2016 between forces loyal to President Kiir and those loyal to Machar who is a former South Sudan People’s Liberation Army rebel leader. To quell the renewed conflict, the two went on to sign a peace agreement in September 2018. However, implementation of the agreement was delayed.

November 12, 2019 was intended to be the day South Sudan made a decisive break with the past by implementing the peace deal and forming a unity government. Kiir, Machar (who now leads the official opposition), and other small groups had agreed to finally form a transitional government of national unity but they missed the opportunity again. Machar would have been reinstated as first vice president in the new government.

As the deadline drew closer, sticking points like the integration of a trained unified army, general security and the demarcation of borders between States proved difficult to resolve. Machar and Secretary General of South Sudan’s Opposition Alliance Lam Akol called for the formation of the government to be delayed over fears that full-scale conflict could occur.

But Kiir continued pressing towards the November 12 deadline. In October, the president claimed his government and the opposition were on schedule to form the transitional government by the deadline.

Machar’s opposition troops had already started moving to the agreed cantonment sites as part of the unified force, but some troops have started deserting sites without training. Fears were raised that the absence of a unified army would threaten the sound formation of the transitional government.

Eventually, Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni – one of the guarantors of the transitional agreement – the regional Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), and the South Sudanese leadership agreed to delay forming a government of national unity for 100 days.

It is unlikely that South Sudan will resolve all the outstanding issues within 100 days. It needs to establish a unified, trained army and the opposition soldiers who have left the cantonment sites need to return. Further, the president must make a better effort to integrate government troops into the unified force. In addition, a long-term strategy around disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration is urgently required. South Sudan doesn’t have the funds or resources to meet these requirements in 100 days.

Doomed from the start

According to the 2018 Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan the transitional government was to be implemented in two phases. The current pre-transitional phase should determine the number and location of cantonment sites; screening, training and reunification of armed groups; and the number of South Sudanese states.

The second phase is supposed to include three years of a Revitalised Transnational Government of National Unity. After that three-year period national elections should be held. According to the agreement, Kiir cannot form a government without including Machar.

This has been a point of contention because the two men have not had a cordial relationship since 2013 when President Kiir dismissed former vice president Machar for allegedly attempting a coup.

Another obstacle in the path of a transitional government has been Kiir’s disregard for IGAD’s role in the peace process. The authority comprises Djibouti, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya, Somalia, the Sudan, South Sudan and Uganda.

In October, he created a committee to look into the number of states and boundaries despite the fact that the boundaries commission (chaired by IGAD) had already agreed to reinstate the 10-state system. The current 32-state system has caused problems around the appropriation and ownership of ancestral land.

But South Sudan’s biggest problem is the demands of elites within the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army. Every attempt for peace has been scuttled by a corrupt leadership. This has led to more violence and increased fragmentation among their supporters.

Obstacles ahead

One hundred days is not enough time for the Kiir and Machar factions to come to a new agreement. Generally, the reformation of states in conflict is complex and so far South Sudan has been unable to grapple with this complexity.

The country must resolve the thorny issue of fragmented militias which have become increasingly localised. It must also think critically about holding a general election in three years as proposed by the current peace agreement. Calling for elections in a country as fragile as South Sudan will only lead to further infighting.

In addition, the number of states is still unresolved. This is problematic because the recognition of a fixed number of states is essential to how the country will be governed.

Further, the current peace agreement, which establishes the transitional government, needs to be integrated into the transitional constitution if the new government is to be recognised as a legitimate authority.

Future prospects

Overall, establishing a federal and democratic system of government will be a hard mountain for South Sudan to climb. The country has barely experienced good governance, constitutionalism, rule of law, human rights and gender equity. It will require strategic and implementable agreements to get back on track.

Now might be the time for South Sudan to consider an external custodian government to build institutions and reform security mechanisms. This has happened before in warring Cambodia when the United Nations established a transitional authority in 1992, leading to a comprehensive political settlement.

The South Sudanese peace process might be resolved by a similar initiative led either by the UN or the African Union. It would enforce rule of law and implement a sound political strategy for peace. Thus far, the peace agreements between local and regional actors have been unable to implement this kind of change.

Andrew Edward Tchie, Research Fellow for Conflict, Security and Development at IISS, King’s College London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.