Andrew Edward Tchie, University of Essex

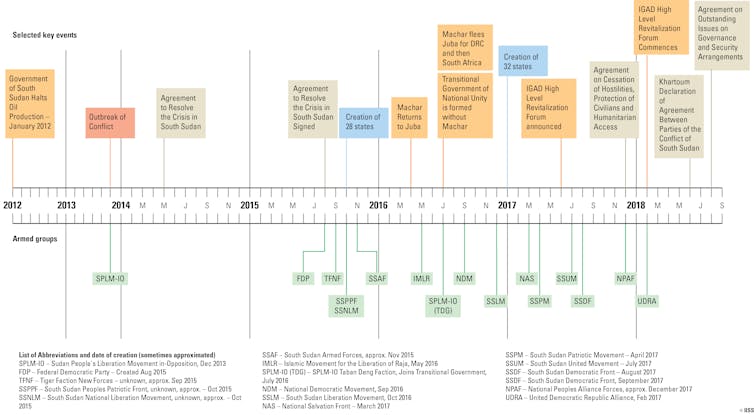

South Sudan plunged into conflict in 2013 after President Salva Kiir accused his deputy Riek Machar of an attempted coup d’etat. After five years in which regional powers sought ways to end the stalemate, Kiir and Machar signed the latest in a series of power-sharing peace agreements.

The rivals have agreed to form a transitional government of national unity. Machar – who initially fled the country in 2016 – will be reinstated as first vice president. He will serve alongside four other vice presidents and a reconstituted transitional government is set to be established in May 2019.

However, serious questions remain over the new agreement’s chances of success. Dubbed, the “revitalised agreement” the pact is simply a recycling of the 2015 peace deal which promised an end to the conflict that has displaced one-third of the population.

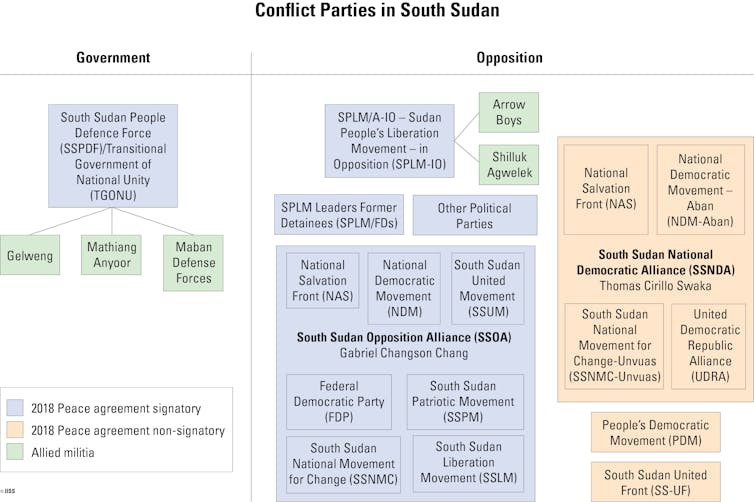

The current agreement has less accountability mechanisms, limited provisions for disarmament and demobilisation of armed groups, and no reintegration plan. In addition, there are no penalties for those who do not comply. But most importantly, the agreement does not address the power sharing wrangles within the ruling Sudan People’s Liberation Movement, which i the root cause of the conflict.

Two days after the agreement was signed fighting continued and violence returned to parts of South Sudan. Despite the ceasefire, the government launched attacks on the militant National Salvation Front in central and western Equatoria where humanitarian workers have been attacked.

Successive ceasefires since the 2013 conflict have been violated by all sides. In December 2017, for instance, a peace deal collapsed shortly after signing with Machar’s opposition forces claimed that the government broke the ceasefire. The government claimed that the rebels attacked first.

If the country’s recent history is anything to go by, the revitalised agreement is likely to suffer the same fate as previous peace deals, all of which have failed.

South Sudan’s ruling elites have spent decades declaring war and making peace. If concrete steps aren’t taken to achieve the latest agreement, then the country will once again descend into anarchy.

Why deal will fail

It will be difficult to make the agreement stick given the environment in South Sudan, a country which has become the most dangerous for humanitarian air works.

One of the reasons is that the military and political elites in the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) have developed a taste for amassing wealth through lucrative government posts.

They are able to do this because SPLM has absolute control over the executive and legislative arms of government. This excludes Machar and his SPLM-In Opposition wing from making national decisions and accessing state resources.

In addition, the agreement doesn’t fully address the emergence and complexity of new rebel groups. Eighteen large groups have emerged since the conflict started in 2013. Unless a single dominant group emerges, it will be only a matter of time before fighting breaks out again.

Then there is the question of implementation. The revitalised agreement promises the creation of a new “national army” within eight months. But it says nothing about how this army will be created. While both Kiir and Machar agree in principle that Sudan should be one fighting force, they don’t agree on how the new army will be constituted.

Various ideas have been floated. One includes a proposal by the Army Chief of Staff, Paul Malong, to disband the existing army and reconstitute it based on ethnic and community representation. But as things stand there is still no road map to a new army.

The most recent agreement also says that national elections must take place after a three-year transitional period. Pushing for elections could further displace civilians and speed up the use of violence against civilians as parties compete for votes. Despite this possibility the agreement doesn’t provide for a peacekeeping mechanism to prevent violence during the transition.

Another thing standing in the way of peace is foreign interference. Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir and Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni have a history of supporting opposing sides in South Sudan’s conflict.

A recent report found that despite a UN arms embargo on South Sudan, weapons are still making their way into the country via Uganda. President al-Bashir, on the other hand, has been known to support many of Machar’s rebel generals. At the heart of this external push and pull is the desire to access South Sudan’s vast oil wealth.

South Sudan’s vast oil reserves also fuel ethnic tensions. Ethnic divisions continue to be an obstacle to a lasting peace. As long as peace deals like this one are more focused on power sharing rather than the equitable distribution of resources to all ethnic groups they will continue to fail.

Finally, there are no monitoring and enforcement mechanisms in place to hold the government of national unity in check. The agreement leaves it up to the parties to self-monitor. This makes it harder for the African Union and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) to support the ceasefire. IGAD is an eight-country African trade bloc that provides a strategic and integrated framework for regional cooperation. It comprises the governments of Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan and Uganda.

Path to success

For the agreement to succeed the government and its partners must adopt a strategy that will improve the social economic status of the country and support the creation of sustainable peace at the same time. This will require support from the international community to prevent fragmentation of society, provide stability for the election period, and strengthen external monitoring mechanisms.

The international community, particularly the US, can also offer technical support for local structures, rebuild local institutions, and support social cohesion in the long term. This would include helping South Sudan to diversify its economy away from a dependency on oil.

Creating a new national army and recasting former rebel groups as bona fide military forces as the South Sudan People’s Defence Forces, while neglecting to address ethnic tensions, divided loyalties, and entrenched hostility will not pave a clear pathway to peace.

To give peace a chance, the government must acknowledge its support of mercenaries who contributed to the violence. It must also take steps to address the historical grievances of the people of South Sudan.

Andrew Edward Tchie, Editor, Armed Conflict Database; Research Fellow, Conflict, Security and Development at International Institute for Strategic Studies, University of Essex

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.