Chris Colvin, Queen’s University Belfast and Eoin McLaughlin, University College Cork

As news of the global spread of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) emerged, global financial markets reacted pessimistically and behaved in ways not seen since the 2008 financial crisis. But fully understanding the potential future economic impact of the virus which leads to this disease remains difficult – because spread of a disease on this scale is unprecedented in the modern world.

The closest parallel is the 1918 influenza pandemic, popularly known as the Spanish flu (because it was first reported in Spanish newspapers). So what are the lessons from this historical pandemic for policymakers today?

The 1918 flu was the last truly global pandemic, its potency exacerbated in an era before the existence of international public health bodies such as the World Health Organisation. About one-third of the world’s population caught this acute respiratory tract infection.

Conservative estimates put the death toll at 20 million, but it could have been more in the region of 50 million. By comparison, nine million people died in combat during the entirely of the first world war.

Probably about 2-3% of those who caught this RNA virus ended up dying, but much of the mortality was the result of complications – such as pneumonia – rather than the flu itself. There were several waves of flu and most deaths occurred within a week of each outbreak. The last outbreaks, in 1919, took place a year after the disease was first identified.

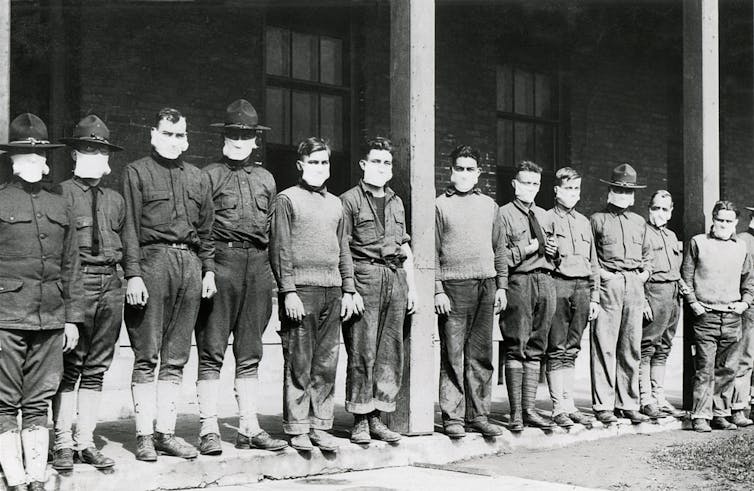

The pandemic spread globally because of the particular set of circumstances in which it first arose. The first world war had just ended and entire armies were being demobilised, returning home with the disease. Outbreaks spread along major transportation routes.

Much of the world’s population was already weak and susceptible to disease because of wartime strains, especially in Germany. To make matters worse, there was an absence in transparency and little policy coordination. Wartime media censorship was still in force and governments were preoccupied with planning for the peace.

Those who perished were typically in the prime of their lives, between 15 and 40 years of age. Aside from these deaths, exposure to the flu had serious permanent long-term physical and mental health consequences on many survivors, especially the very young. There were also immediate and long-term consequences for the economy.

Urban populations proved particularly susceptible to this strain of flu, partly because of pollution. Researchers recently found that many more people died in the more polluted cities in 1918 relative to less polluted urban areas, suggesting a direct link between air pollution and influenza infection.

Economic consequences

The immediate economic consequences of 1918 stemmed from the panic surrounding the spread of the flu. Large US cities, including New York and Philadelphia, were essentially temporarily shut down as their populations became bedridden. As in Italy now, businesses were closed, sporting events cancelled and private gatherings – including funerals – banned to stem the spread of the disease.

The economic consequences of the pandemic included labour shortages and wage increases, but also the increased use of social security systems. Economic historians do not agree on a headline figure for lost GDP because the effects of the flu are hard to disentangle from the confounding impact of the first world war.

The long-term consequences proved horrific. A surprisingly high proportion of adult health and cognitive ability is determined before we are even born. Research has shown the flu-born cohort achieved lower educational attainment by adulthood, experienced increased rates of physical disability, enjoyed lower lifetime income and a lower socioeconomic status than those born immediately before and after the flu pandemic.

Three lessons from the past

The lessons from 1918 are stark. First, the public health response to the spread of the disease must focus on containment. The reason why the 1918 pandemic resulted in so many deaths was that so many people caught the disease in the first place.

They were exposed because policymakers failed to stop the spread. Indeed, their actions helped spread the flu more widely. The repatriation of troops to their countries of origin was probably the main culprit.

Communicable disease control policy works. Researchers found that US cities which implemented efforts to reduce infectious contact between people early in the 1918 outbreak had significantly lower peak death rates than cities that were later to adopt disease containment policies.

The second lesson is that good information is key to disease control. We cannot afford a media blackout or, worse, an active disinformation campaign. We can already see the terrible consequences of such policies in Iran.

The truth always comes out eventually – there is nothing to be gained from hiding it. Indeed, governments stand to lose if censorship leads to social unrest. Political scientists are already speculating on the long-term political impact of media manipulation of coronavirus news in China.

Preparing for the worst-case scenario

The third lesson is that we must prepare for the economic and human consequences of the virus and act to minimise its impact. This pandemic is both a shock to demand and supply. Just as the disease is highly contagious, so too is the economic crisis it causes.

The labour lost from implementing the recommended 14 days of self-isolation for suspected cases alone will have serious economic implications. Closing down entire regions or countries, as recently enacted in Italy, will no doubt cause a recession.

The emergency lowering of interest rates in the US and the UK must be the first of many policies aimed at mitigating the economic impact of COVID-19. New fiscal policy measures must now also come into play. Individuals in low-paid precarious employment deserve targeted attention. Where medical care and sick leave are costly, this can force people to go to work even if they are still carrying the virus.

Just as in 1918, people in more polluted, urban, areas are likely to be particularly at risk. These are populations that are already more susceptible to respiratory illness due to environmental factors. Special measures to help these groups must be considered.

And babies born to those affected by flu must be monitored closely and remedial interventions designed. We should not just focus on the headline mortality rates. We need to pay attention to those who survive this pandemic, and their offspring too.

Chris Colvin, Senior Lecturer in Economics, Queen’s University Belfast and Eoin McLaughlin, Senior Lecturer in Economics, University College Cork

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.