Anthony Ellis, University of Salford

In the wake of several fatal knife attacks, UK Prime Minister Theresa May was criticised for claiming they weren’t related to cuts to police numbers. These deaths are undoubtedly the result of many different factors, but they are the most recent cases of an overall trend of rising violence in England and Wales.

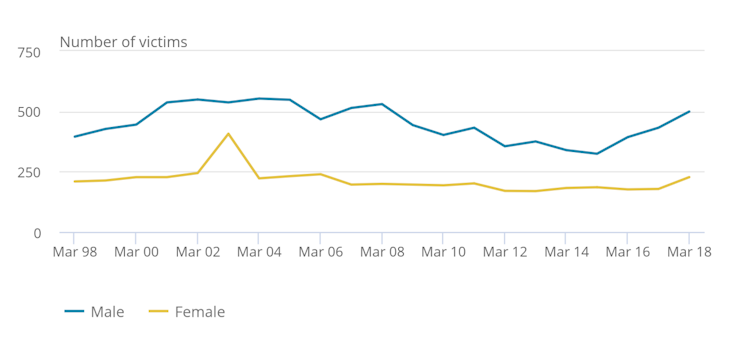

The UK’s homicide rate had been declining since 2003, but there has been a steady year-on-year increase since March 2015 and this has affected young men in particular.

The reasons for this are complex, but previous periods when there were sustained increases in the number of homicides per year may reflect changes in society that are relevant to today’s trend.

Based on data collected between 2017-2018, the rate at which men are currently being killed by violence is over double that for women – 17 and eight people per million population respectively. This pattern becomes more pronounced when we consider the ages of victims.

Young people aged 16-24 experienced the largest volume of increases from March 2017 to March 2018, closely followed by those aged 25-34. For the perpetrators of violent crime, a similar demographic pattern emerges. Over half of all those convicted of homicide during this latest measurement period were male and aged between 16-34 – 33% were 16-24 and 26% were 25-34.

The Home Office’s Homicide Index doesn’t detail the social backgrounds of victims and perpetrators, but research indicates there’s a greater chance of being killed by violence the poorer you are.

Homicide is thankfully still a rare crime in England and Wales, particularly when compared with other countries. But these comparatively low national rates overlook the fact that working class men remain at much greater risk of dying as a result of violent behaviour than the British population at large.

Media depictions of homicide often concentrate on the relationship between perpetrators and victims, or are concerned with the biographies of those who kill in search of their motivations. Such analyses are interesting and potentially useful, but they effectively individualise the issue – something that provides very few details about the social contexts in which homicides happen and in which rates increase and decrease.

Murder rates do not go up or down for no reason, nor can they be attributed solely to the motivations of a minority of people. Changes in society and the economy can affect the opportunities and motivations to harm others.

Wider social context

Danny Dorling, a professor at Oxford University who studies social change, argues that homicide rates are a “social marker” that can tell us a lot about societies and how they’re changing.

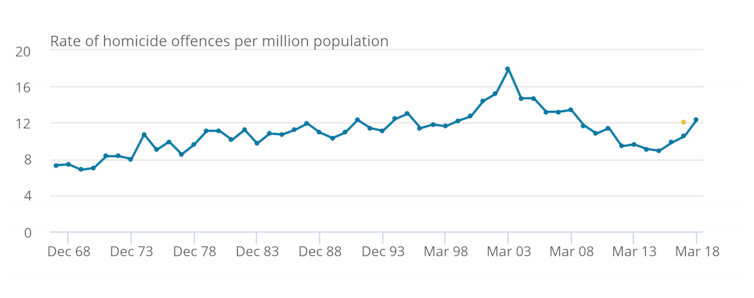

From the late 1960s until the early 2000s, the rate of homicide in England and Wales steadily increased. The rate fluctuated slightly year-to-year during this period, but the overall pattern throughout the latter half of the 20th century was a steady incline.

Dorling’s research showed that increases in the homicide rate between 1981 and 2001 were concentrated almost exclusively among working age men living in the poorest parts of the country. During the 1980s, Britain was reeling from a global economic recession and subject to a restructuring of its economy which had significant consequences for everyday life.

The era of Margaret Thatcher’s leadership was marked by growing inequality and the reduced political influence of working class communities. Dorling argued these changes increased poorer men’s risks of being murdered.

Where there’s enhanced inequalities in wealth, status and opportunities, there is a much greater likelihood people will feel worthless, humiliated, disconnected from others and less obliged to follow society’s rules.

Contemporary rises in lethal violence, once again, largely involve the “usual suspects” – young and disadvantaged men killing and being killed. Austerity cuts to public services since 2010 have disproportionately affected poorer communities. The impact of this on homicide rates among poorer men must be considered carefully.

Modern culture, which values material goods and personal success, may amplify the effects of austerity and inequality. An enduring mantra from the 1980s is that there is no such thing as society, just self-reliant individuals.

The justifications given by young men who carry and use weapons tend to reflect this kind of individualism. Violent men I have interviewed describe their use of violence in individualistic terms – violence as a means to establish personal reputations and status.

The sharp rise in homicide among disadvantaged young men since 2015 correlates with intensifying austerity. Like men who came of age during the 1980s, today’s disadvantaged youth have grown up in the aftermath of a global recession and amid austerity that has limited their prospects.

This raises another tragic reality of rising violence today. As during previous rises, largely disadvantaged and insecure young men are competing with one another for reputation and social status. In the process, they’re turning on men just as disadvantaged, economically marginalised and politically abandoned as them.

Anthony Ellis, Lecturer in Sociology and Criminology, University of Salford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.