The transfer of power from the APC to ruling SLPP has brought with it protests, walkouts, boycotts and low-level violence.

A year since President Julius Maada Bio defeated the incumbent in general elections and took office, Sierra Leone’s political scene is fraught with tensions. As the now ruling Sierra Leone People’s Party (SLPP) has gradually wrested control from the former ruling All People’s Congress (APC), political relations within the country have soured dramatically.

On 31 December 2018, for example, opposition supporters took to the streets of the capital Freetown to protest against the arrest of a former minister. Things deteriorated from there. This March, a disputed by-election in Kambia district prompted the APC to declare a boycott on future elections. A few days later, the party demonstrated against the government’s attempt to remove over a dozen of its MPs for alleged electoral malpractice. And then, on 26 March, all the APC’s 68 MPs walked out of parliament in protest.

These events demonstrate the difficulties than can arise from transfers of power after elections. Sierra Leone’s change of government has led to several APC officials – from low- to high-level bureaucrats across various ministries, departments and agencies – being sacked or moved. Meanwhile, the heads of sometimes very local organisations and unions – such as those representing drivers, petty traders and money exchangers – have also been replaced or pressured, demonstrating the SLPP’s formidable grassroots structure and determination.

At the core of much political tension, however, is a Commission of Inquiry set up to investigate corruption between September 2007 and April 2018 – i.e. the latest period of APC rule. The SLPP government has shown it is taking this measure seriously. In April 2018, a transition report named various former APC officials accused of corruption, which was followed up with several high-level arrests, including of former ministers, an ambassadorand bank director. At the same time, the Anti-Corruption Commission engaged in unprecedented levels of activity, inviting individuals such as former president Ernest Bai Koromo to give testimony.

For its part, the APC has refused to appear before the Commission of Inquiry until “certain conditions are met” relating to the body’s mandate. Nonetheless, it is conceivable that large numbers of senior APC politicians will be banned from politics and required to repay large sums of money.

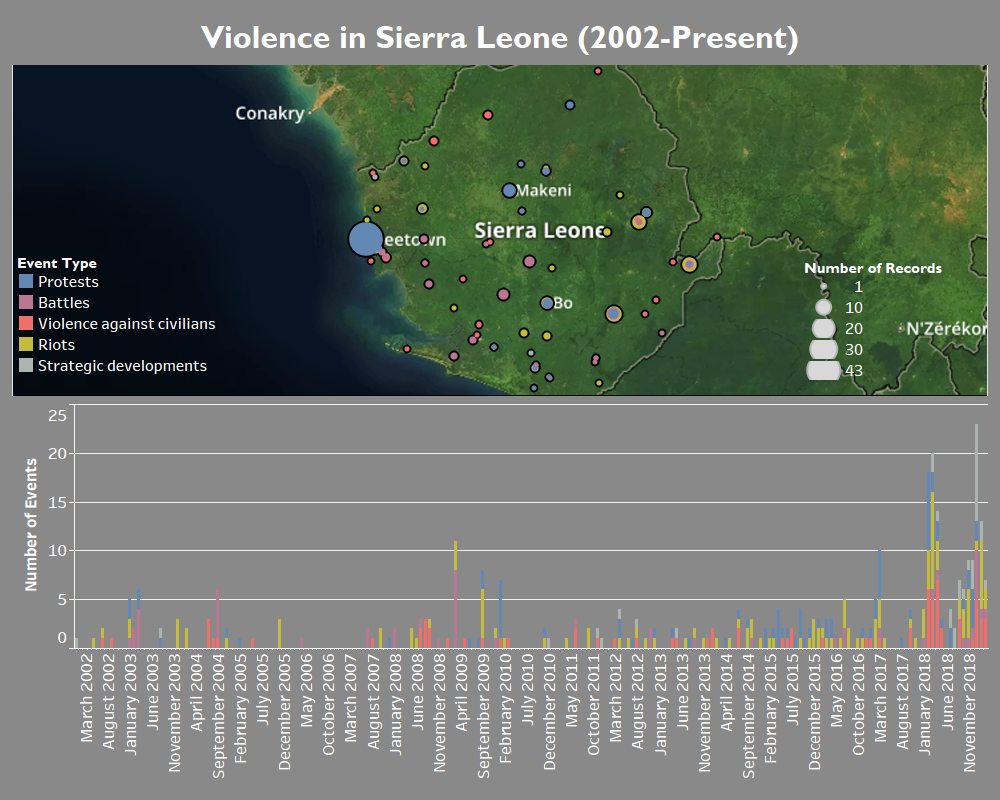

While this is going on, Sierra Leone is also witnessing a rise in small-scale violence. Data from ACLED, supplemented by information from local organisations, suggests that political violence has risen since 2013-2014, possibly as politicians began employing gangs. This accelerated, however, in the build-up to the March 2018 elections and has not reduced since. These clashes are not limited to one political group and have occurred across the country (see graphic below).

This low-level violence typically arises around contentious local issues such as the leadership of markets or student union elections. It does not challenge the state and is not organised around armed groups. Rather, it is driven by different groups such as formal party security (often trained ex-combatants), informal party “Task Forces” (violent youth groups) or secret societies. Some of this violence is also increasingly conducted by gangs who are often hired by politicians to start riots, “organise crowds” or intimidate opponents.

Sierra Leone’s fraught politics and ongoing low-level violence pose serious concerns, but for the moment, both seem relatively contained.

Politically, the APC seems too divided to mount a sustained challenge to the SLPP. Internal competition to succeed their former leader Koroma continues to create internal divisions. The main faction is formed around the ex-president and appeals in particular to the Loko and some Limba and Temne people in Bombali. This group holds the most power and is primarily behind the walk-outs, election boycott and threat of riots.

A second faction is also Temne-based but stems from Port Loko (with support from Temne in Tonkolili). Meanwhile, a third group cuts across these divisions and contains APC members who remained loyal during the 1991–2002 civil war unlike those, like Koroma, who joined alternative parties.

In terms of violence, it also seems unlikely that political tension will translate into significantly increased instability. President Maada Bio and his faction – known as paopa – has tight control over the security realm with party intelligence networks in many places. There are claims of ethno-regional rifts within the military and police, but Bio’s decision to keep the APC-appointed head of the army and police (controlling subordinates who generally oppose the SLPP) suggests he can walk this tightrope.

Similarly, paopa has dealt cleverly with ex-combatants in the APC task forces and presidential police; many perceive the APC to have the highest rankings war-commanders and most notorious ex-combatants, but paopahas been able to dislodge some of them, partly by confrontation and partly by co-optation. Bio has also proven adept in handling political gangs. Before the elections, all three main gangs in the country – the So So Black (Black), Member of Blood (Red) and Cent Coast Cribs (Blue) – were loyal to the APC, but most black and blue hoods in Freetown have now sided with the SLPP.

For now then, the SLPP appears to have the upper hand and despite tensions, Sierra Leone’s broader stability seems not to be under threat. Looking ahead, however, there may also emerge new sources of friction.

Within the SLPP, for instance, there are some seasoned and prominent politicians who dislike Bio and fear his uncompromising stance could lead to a backlash. The regime could seek to replace them, possibly leading to infighting. Some ruling party youth and task forces also complain about the many diaspora appointments. Some young politicians may seek to exploit this discontent in a bid to rise to party prominence.

Meanwhile, it is still possible that the fear of losing further power could convince APC elites to overcome their differences, at least temporarily. There are rumours that the opposition’s decision to boycott elections and walk out of parliament were part of an attempt to provoke the SLPP into overreacting in the hope this could elicit national and international sympathy.

Kars de Bruijne is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Sussex and a senior research analyst at the Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset (ACLED).

This article is republished from African Arguments under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.