Rockford Weitz, Tufts University

Tensions between the United States, Iran and other countries are flaring again in the Strait of Hormuz.

There are competing explanations for what’s going on in the narrow seaway through which 21% of the world’s crude oil currently passes.

Most of the reports of attacked tankers, smuggled oil and downed drones involve Iran and the United States. But the oil and the tankers involved also belong to other countries, including Japan, Norway and the U.K.

As a researcher who studies strategic maritime chokepoints like this one in the Middle East, I consider the ongoing skirmishes in this waterway to be classic examples of Iran’s use of hybrid warfare – unconventional tactics that are too subtle to trigger military retaliation.

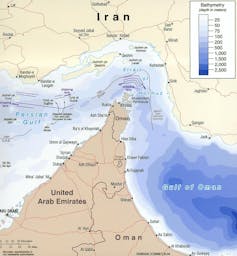

A 21-mile-wide waterway

This 21-mile-wide channel connects the Indian Ocean with the Gulf. For all of recorded history, it has connected Arab and Persian civilizations with the Indian subcontinent and Pacific Asia. For example, before the rise of European seaborne empires in the 15th and 16th centuries, porcelain from China and spices from the Indochina peninsula often passed through the strait on the way to Central Asia and Europe.

Today the Strait of Hormuz separates Iran from the countries of Oman and the United Arab Emirates, which have strong military ties with the United States.

All shipping traffic from energy-rich Gulf countries converges in the strait, including crude oil and liquefied natural gas exports from Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

This maritime chokepoint became an arena of conflict during the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s. Each side in the so-called “Tanker War” tried to sink the other’s energy exports. To avoid being targeted, Kuwaiti oil tankers were re-flagged under the U.S. shipping registry, obscuring their true ownership.

Although crude oil continued to flow, marine insurance rates for vessels operating in the strait spiked by as much as 400%.

What is happening now?

The latest conflicts in the Strait of Hormuz arose after the Trump administration’s decision to leave the Iran nuclear deal in May 2018. When Iran struck that accord in 2015 with the U.S., U.K., Russia, France, China, Germany and the European Union, it agreed to restrict its nuclear development in exchange for the lifting economic sanctions against it.

By July 2018, Iran had threatened to close the Strait of Hormuz to retaliate against the ratcheting up of U.S. sanctions against it.

By engaging in hybrid warfare, Iran appears to have already begun to disrupt trade flows through the strait and raise the diplomatic stakes.

Notably, the June 2019 attacks on Japanese and Norwegian-owned oil tankers coincided with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s visit to Tehran. Iran denies any involvement in those attacks, but the U.S. released video footage it said showed Iranian special forces removing an unexploded mine from one of the tanker’s hulls – and alleged it was most likely doing so to remove evidence.

In my view, if Iran did indeed conduct the attacks, it could be a signal to influential Asian powers, especially Japan and China, that they need to further pressure the Trump administration to ease sanctions against Iran – or risk disruptions to vital oil and gas exports to Asia transiting the Strait of Hormuz.

Iran would certainly have trouble stopping all shipping through the strait. Modern cargo vessels are massive and difficult to disable. Unlike in the 1980s, most oil tankers now have double hulls, making them harder to sink. Furthermore the U.S. is building a multinational coalition to protect commercial shipping transiting the Strait of Hormuz as well as waters around Yemen.

And the fact that both the U.S. and Iran say they want to find a diplomatic solution suggests that neither side wants to see the conflict escalate into a full-blown war.

Are consumers in the United States and other countries likely to suffer because of these tensions in the Strait of Hormuz? So far, that has not been the case in terms of fuel costs. Global oil and natural gas prices declined in the first six months of 2019 despite tensions in the Gulf due to a growth in supply.

Portions of this article appeared in a related article published on July 9, 2018.

Rockford Weitz, Professor of Practice & Director, Fletcher Maritime Studies Program, The Fletcher School, Tufts University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.