Kylie Thomas, University of the Free State

A South African court has ruled that a security policeman has to stand trial for his role in the killing of an anti-apartheid activist nearly 48 years ago. It’s a judgment that will have far-reaching implications for unresolved cases of human rights abuses under apartheid. The case also draws attention to the enduring effects of apartheid-era policing practices and the prevalence of torture in South Africa today, 25 years after the transition to democracy in 1994.

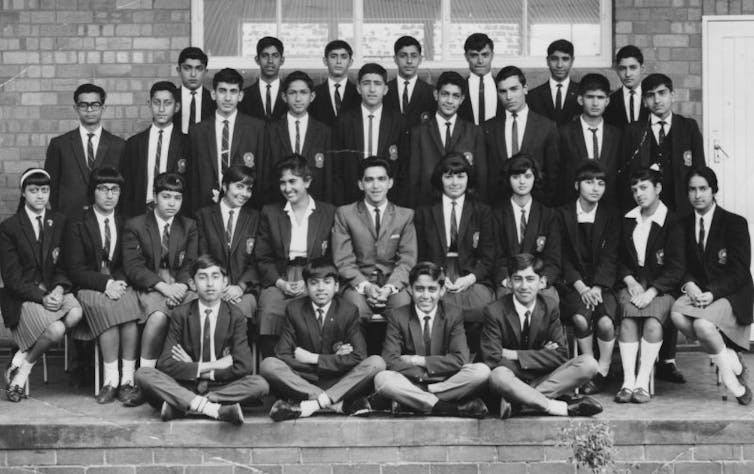

In 1971 the Security Police claimed that Ahmed Timol had committed suicide by throwing himself out of the window of room 1026 of John Vorster Square, the notorious police headquarters in central Johannesburg. In 2017, more than 40 years after his death, the case was re-opened. The court established that Timol had been tortured and murdered. Former security branch sergeant Joao “Jan” Rodrigues, allegedly the last person to have seen Timol before his death, sought a permanent stay of prosecution for his part in the murder.

The judgment states that,

the interests of justice and the societal need to ensure accountability for the commission of serious offences and the nature of the crime located in its historical context all militate against the granting of a permanent stay of prosecution.

The judges argued that,

This, in many respects, is a difficult case. Not necessarily on account of the legal issues it raises, but rather to the extent that it compels us to revisit our troubled past; examine what occurred there, recognise the need for reconciliation; and the consequences that invariably went with it.

The judges added:

Importantly, this case reaffirms that justice and the truth were never meant to be compromised during all that our young society sought to do in dealing with its troubled, turbulent and shameful past.

Pursuing justice

The verdict is a hard-won victory for the Timol family. They have been pursuing justice for over four decades, including at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) hearings in 1996. The TRC was set up in 1995 and made it possible for victims to publicly recount their experiences. Perpetrators of violence could also give testimony and request amnesty from prosecution.

The Security Police officers involved in Timol’s arrest and interrogation did not testify at the TRC, nor did they apply for amnesty for their part in his murder.

The court ruling offers hope for those – like the Timols – who continue to seek the truth about what happened to their loved ones at the hands of the apartheid-era Security Police. It re-opens questions about impunity and accountability that apartheid-era perpetrators hoped would never resurface after the TRC published its final report in 2003.

The TRC handed over 300 cases involving gross violations of human rights to the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA). This was done on the understanding that they would be investigated and that those responsible would be prosecuted.

Policing practices

The return to the unresolved TRC cases is significant not only for how South Africa deals with impunity relating to human rights violations committed under apartheid, but for addressing impunity in the police and justice system today.

The NPA’s failure to pursue the 300-plus cases is a sign of how the impunity that characterised the apartheid state has not yet been expunged. The officers, appointed in 2018 to investigate 20 cases of human rights violations that took place under apartheid, were themselves former members of the Security Branch. This is according to a February 2019 letter written to President Cyril Ramaphosa by 10 former TRC commissioners.

They divulged that:

The most senior investigator had been implicated in the torture of a political detainee in the 1980s. This detainee, together with his wife, were subsequently shot dead by the Security Branch, after he sued the South African Police for damages. Although the two officers have since been removed from these investigations following complaints, it is hardly surprising that no progress has been made in any of these 20 cases. As recent as 2018 it is still business as usual with the TRC cases ultimately controlled by forces from the past.

Torture after apartheid

The continuing prevalence of torture and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment within the South African Police Service (SAPS) indicates both how thoroughly contaminated the organs of the state were under apartheid and how inadequate attempts to transform the police have been.

In spite of the constitutional reforms introduced in 1994, torture has not been eradicated. It continues to characterise policing practices. In 2017/2018, South Africa’s Independent Police Investigative Directorate, an official organisation that is tasked with investigating police abuse, received reports of 3 661 assault cases, 436 cases of death as a result of police action, and 271 cases of torture. The Directorate’s report indicates that there were 98 more incidents of torture in 2017/2018 than in the previous year. Of the 62 cases of torture investigated during 2017, there was only one conviction.

Torture, like corruption, is a practice generally committed by groups, rather than by individuals. Torture is not an aberration. It is systemic, and it persists where civil society, the justice system and the state have failed to expose and punish those who practice it. Torture is an open secret made possible by impunity.

The re-opening of the Timol case and the court’s decision to prevent apartheid-era perpetrators from permanently evading justice is an important sign that the long reign of impunity might at last be coming to an end.

Kylie Thomas, Associate Researcher at the Institute for Reconciliation and Social Justice at the University of the Free State, University of the Free State

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.